“There is a necessity to take scissors to the archive and rethink it,” the cult photographer says as The Rose opens – a new show exploring collage as a powerful tool for protest and repair

Collage can be a powerful means of creative protest. Involving the violent acts of ripping, cutting, and slicing, this rebellious art form sees images transformed to confront the strict cultural codes of their original making. The Rose, an expansive group show at CPW (Center for Photography at Woodstock), brings fifty contemporary artists including Wangechi Mutu, Vija Celmins and Wendy Red Star together with 1960s and 70s trailblazers. The show is curated by artist Justine Kurland and CPW curator Marina Chao – the former worked on a previous iteration with Sarah Miller Meigs and Libby Werbel at The Lumber Room in Portland.

“I have developed as an artist based on the conversations I’ve had with Marina,” says Kurland, who has had a long collaborative relationship with Chao. “She has been doing so much curatorial work shifting our focus towards art that looks at repair, race and gender, and ways we construct realities that too often are unlivable.” Kurland also worked closely with Meigs on the original selection; around half the exhibited work comes from Meigs’ collection, which has been built over 20 years to support women and artists of colour.

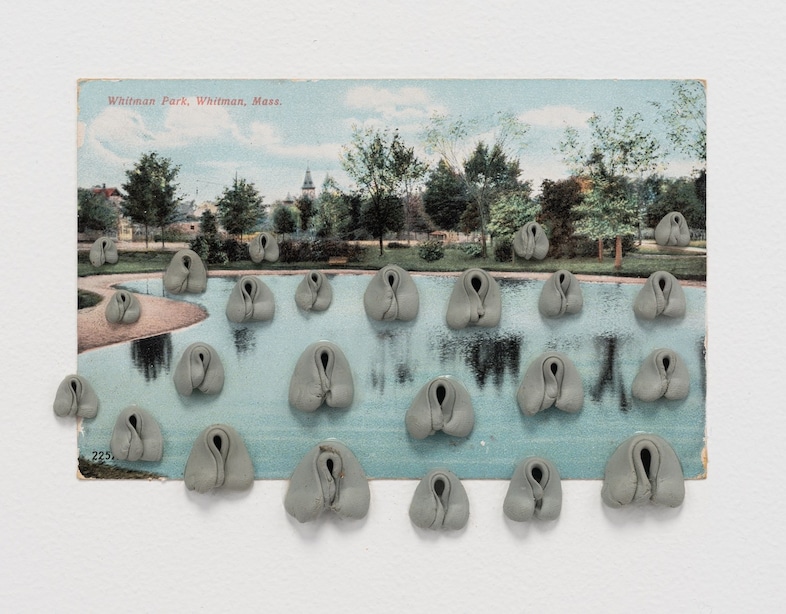

Hannah Wilke is one of the earliest artists in the show. Her at-times humorous collages probe the cultural expectations placed on women’s bodies and labour, embracing raw sexuality and playful liberation. While the show expands beyond traditional cut-and-paste flat images – Joiri Minaya’s #dominicanwomengooglesearch (2016), for example, features UV prints taking up three-dimensional space in the room – the curators see circular and meandering threads between the old and new guards, rather than strict chronological progression.

“We have talked a lot about circularity, things with no beginning and no end,” says Chao. “All these feminist artists are passing this tradition on and on, formally and conceptually.” Of course, the digital world has changed how we understand multiple images and overlays. Chao’s previous shows have contested the idea of a unified image in the contemporary world. She mentions collage, double exposures, shadows, digital avatars and AI as ways of escaping reductive depictions and creating new ways of talking about the body.

Kurland’s own work attempts to challenge the canon. She embraced collage in her art practice after 30 years of taking photographs, cutting up her own books. “I really wanted to disrupt this notion that Picasso invented collages,” she says. “The circularity of our show has a lot to do with how women, queer artists and people of colour have been marginalised. There is a necessity to take scissors to the archive and rethink it.” Chao similarly highlights the generative act involved in collage. “It’s such a productive method, because there is the violence and ripping but there’s also the repair and constructing. You care very much about putting these things together in a different way.”

Both curators are excited to have a selection of Carla Williams’ collages in the show which have never been exhibited. “She’s such an important artist,” says Kurland. “In the 1980s, she was a queer Black woman going to Princeton, learning about the history of photography. She didn’t see herself represented in any of the work from the 1920s, 30s, 40s … so she made these self-portraits where she went through the rolodex of history and remade every stylistic trope to correct the archive.” Through collage, Williams presented herself as the cliched female nude and in more formal portraiture poses. A series of works show her with parts of her face painted white, drawing parallels with Frantz Fanon’s Black Skin, White Masks, exploring double consciousness, the racialised idea of representation, and the body as contested ground. “Her work is so generative, deep, expressive, sexual, strong and intelligent,” says Kurland. “What is so appealing to me about collage is this way of disrupting, breaking open and correcting an archive.”

There are numerous artists in the show who use their own faces and bodies in collage, such as Shala Miller. The radical feminists of the 1960s and 70s were at times criticised for this, seen to be playing into the male gaze. But as Chao says, now it’s more understood to be “about reclamation”. She also highlights how artists such as Gretchen Bender were able to speak about the body without always showing it. Bender’s Body Ownership series of works placed text over television broadcasts. “She’s talking about the body but also absenting the body, and it is so effective,” says Kurland.

At a time when women’s bodily autonomy, LGBTQ+ individuals and people of colour are severely under attack in the United States, the curators see collage as an important medium. “I think that’s at the heart of the show,” says Kurland. “Reproductive rights are being taken away. LGBTQ+ student clubs in Texas are now banned. ICE is taking protesters from school campuses who are completely legal to be here. We are at war.” Chao agrees. “This show feels hopeful. It feels like the right kind of destructive and reparative potential in this moment.”

The Rose is on view at The Center for Photography at Woodstock until 31 August 2025.